“Reflecting on Abdel Goddous Al-Khatim’s “Reflections On Sudanese Culture

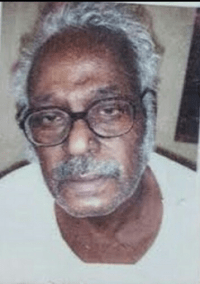

Abdel Goddous al-Khatim is one of the most influential literary critics in Sudan, and he has made colossal contribution to Sudanese literature. He has written a number of well-considered critiques that have placed him among the top critical voices in post-independence Sudan.

Born in the mid-1940s, al-Khatim studied at the University of Khartoum and then at the University of Central London. He worked for the Ministry of Culture in Khartoum and in the Office of the Sudanese Cultural Attaché in London. He has published two books: his 1977 Critical Essays (republished in 2010) and his 2012 Reflections on Sudanese Culture (Abdel Karim Mirghani Cultural Centre). He won several awards, including the Switzerland Intellectual Property Award, and was honored by Tayeb Salih International Award for Creative Writing.

‘Reflections on Sudanese Culture’

The short Reflections — just 134 pages — is divided into three sections. The main part includes 29 critiques of the Sudanese literary and cultural scene from the early 1930s to the present. The second part is a selection of English poems translated by the author, including works by poets like W. B. Yeats, Karl Shapiro, Alexander Pushkin, and Vladislav Khodasevich, while the third section is primarily a compilation of press interviews with the author.

In the first part, al-Khatim seems bothered that Sudanese literary criticism has not built a sustainable flow that can serve as a solid platform for continuous critical discourse. In the presence of such a platform, he argues, “we would not need to prove that al-Mahjoub was the first to write a foot poem in the Arab World, and that Muawia Mohammed Nour was the first to introduce the stream of consciousness into the modern Arab story. Nor would we have trouble tracing the beginnings of cultural criticism in Sudan to the writings of Mohammed Ashri al-Siddiq.”

To al-Khatim, the story begins as early as the 1930s, when pioneer critic Mohammed Ashri al-Siddiq started to shine. He emerged as a critic of note, who had a unique style, characterized by composure and thoughtful reflection. Al-Khatim pays tribute to another pioneer, Mohammed Mohammed Ali, who he describes as “a man of dialectical mentality that pierced into the heart of things,” and “a skillful swimmer against the current.” An example of his unorthodox views is his description of al-Tigani’s poetry as abstruse. However, he later excuses this by citing his youth and limited experience.

When independence came, al-Khatim said, things changed. He refers to “the phenomenon of political and literary splits that emerged strongly after independence,” noting that the civil service gave birth to an elite class that separated itself from the public and lived in ivory towers. The Sudanese culture, he writes, continues to suffer from a cocktail of chronic diseases such as social schizophrenia, division, exclusion, ambivalence, regionalism and tribalism.

The author emphatically calls for rewriting both old and contemporary Sudanese history to wipe out the tribal sediments and to document untold stories (the history of the neglected history), as “the past is valueless if it only aims to justify the present.”

It’s in this context that al-Khatim celebrates Wrath, a novel by Shawgi Badri, as a bold attempt to address the issue of slavery in an extremely candid manner. Employing stark realism, the narrative decried flagrant acts against the dignity of the marginalized and unearthed the tragedies, misery, and deprivation that was prevalent at the bottom of the old city of Omdurman.

Stories singled out

Al-Khatim also praised Issa al-Hilo’s pioneering contribution to Sudanese fiction. Making a particular reference to his short story “The Smoke,” from his collection The Angel on his Daily Trip, he described al-Hilo’s language as lively and attention-grabbing — like movie scripts. To the author, al-Hilo was the first to break away from the conventional event-focused storytelling style in favor of internal depth and intensification of the unconscious in character building. “A writer of al-Hilo’s caliber, who has been writing for more than forty years, deserves a new type of critical writings that can capture the mysterious artistic sensitivity that he has woven into the texture of Sudanese fiction.”

Another story that won al-Khatim’s praise was Abdel Aziz Baraka Sakin’s “The Lover” (from his collection A Woman from Cambo Kadees), which was written in a style closest to natural realism.

He also mentioned Abdel Gadir Mohamed Ibrahim as a writer who was particularly smart at imaging troubled personalities. “Ibrahim excelled in writing for children, and was one of the pioneers of that rugged path.”

He draws attention to the novel Tales of al-Musbah Village that can be read at several levels, as it provides a model of the Sudanese village and its evolution since the era of the Blue Sultanate in the 15th century.

As for Tayeb Salih, al-Khatim underlines the need for freeing him from the yoke of short-sighted criticism and naïve media. He believes Salih deserves unbiased criticism that can highlight his genius contributions. “We also need to rid him of the media armies chasing him wherever he went, hounding him with silly questions like ‘Are you Mustafa Saeed?’” Salih often spent incredible time answering such questions and even giving explanation about the intent of his novels.

Reflections on the narrative scene

Reflecting on the Sudanese narrative scene in general, al-Khatim claims that only a few novelists seem to be committed to a certain project. Narratives — with exceptions like Tayeb Salih and Ibrahim Is’haq — lack commitment. He also claims that the Sudanese novelists generally lack a sense of humor, or an ironic and sarcastic touch.

As to biographical writing, the author presents a number of interesting findings. He asserts that biographies of Sudanese writers, politicians and artists draw heavily on collective history and hardly reflect the author’s personality. One notable exception is Babiker Badri, whom the author places, in terms of candidness, at a par with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Sudanese writer Hassan Najeela (in his book Features of Sudanese Society).

He also refers to Bagady’s diary, which raises important issues such as freedom of thought and the press, commitment to the party, and the tragedies in Sudanese political literature after independence. The author argues that the real Sudanese history is still lying in the shelves of National Archives and in some foreign libraries, such as those at the University of Durham and Turkish and Egyptian universities.

One of the articles deals with Mohamed Osman Yassin, author of Memories and Talks, which was dedicated to the memory of Yassin’s lifelong friend, the poet Tawfiq Salih Jibriel. This book presents insights into the emerging nationalist movement in Sudan at that early time, the burgeoning civil service, as well as comparisons between English and Arabic poetry and reflections on the classical music of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven.

Using a combination of methodological and impressionist approaches, the author provides a thorough review of the Sudanese poets of the 1960s, who, in al-Khatim’s opinion, tried their best to bridge the gap between generations. Mohammed al-Mahadi al-Majzoub, for one, was “the legitimate father” of the “the Bush and the Desert” poetic stream. His emotional pieces about Africa were driven not by a search for a political identity but rather by pure longing for the “innocence of early humanity.”

Poetic paths

These critiques closely follow the impact of the ’60s poetry and the evolution of major cultural currents such as the “Bush and the Desert,” which advocated an Afro-Arab identity, followed by “Apademak,” which called for a pure Sudanese culture. The latter subsequently developed into the so-called Sudanism; a term coined by Nuraddin Satti, Ahmed al-Tayeb Zainal Abidin, and Ahmad Saghairoun.

In this context, al-Khatim examines the contribution of Mohammed al-Makki Ibrahim, whom al-Khatim considers a milestone in the history of Sudanese poetry. He closely follows the development of his poetic glossary, artistic maturity and his ability to explore new horizons in poetry. He reflects on Ibrahim’s first collection, Ommati (My Nation), which was influenced by the rising global leftist tide, when socialism and social justice were at the peak of their luster. Capturing that mood, the collection’s underlining tone was outpouring and enthusiastic. The Orchard Hides in the Rose, on the other hand, reflects Ibrahim’s ability to grasp subtle details of life and seamlessly assimilate them into the texture of his poetry. His third collection, I’m Part of Your Nectar, You’re the Orange shows marvelous images and a flow of simple yet captivating language. In the poet’s latest collection, The Tent of Amiriyah, verse transforms into pure music that transcends language restrictions to become a splendid piano concerto.

In a separate article, al-Khatim examines the various voices, echoes, and cultural ethos in Salah Ahmed Ibrahim’s poetry. He directs attention to the main characteristics in Salah’s poetry, which encapsulates mythical, cultural, and philosophical themes from the time of his first anthology (The Ebony Forest), which manifests a strong commitment to and sympathy with the needy and marginalized. The key points addressed in the article are the visionary language, which emerges as roughed-up prose that exudes deep distress and wisdom, and this seems to be an impact of his diligent reading of Whitman’s poems. Salah also deepened his knowledge of global trends and boldly injected new blood into the arteries of the Sudanese poetry of the 1960s. Al-Khatim credits him with introducing the form and the subjects of Haiku.

Conclusion: The diversity of Sudanese culture

Al-Khatim’s Reflections on Sudanese Culture displays the broad array of the Sudanese literary and cultural scene, stretching across post-independence time.

The book presents a discerning and insightful critique that reflects the enormous diversity of Sudanese culture and sheds ample light on its cross-generational voices and visions that continue to navigate the complexities of Sudanese culture and to contexualize its rich potential. A thorough analysis is provided on their diversified stylistic devices, creative techniques, aesthetic values and intelectual delights.

This article has been classified as one of the best 101 notable pieces

.An earlier version of this review appeared on SudaNow and Arablit

Lemya Shammat is an assistant professor and former head of the languages and cultural studies department at King Saud Bin Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah. She has a Ph.D. in English language and linguistics from Khartoum University, writes regularly for a number of Sudanese newspapers, and published a book on literary criticism and discourse analysis (Madarik Press, 2011) and an anthology of flash short stories (Madarat Press, 2014.) She also translates between English and Arabic.